Dara’s (2019) discussion of personal digital assistants (PDAs) focussed on the use of these devices in the personal context. She notes that government does have a “complex” and important role to play in regulating what data and how PDAs gather that data can be allowed. I think this becomes particularly interesting to consider if we look at the state owned institution of the museum.

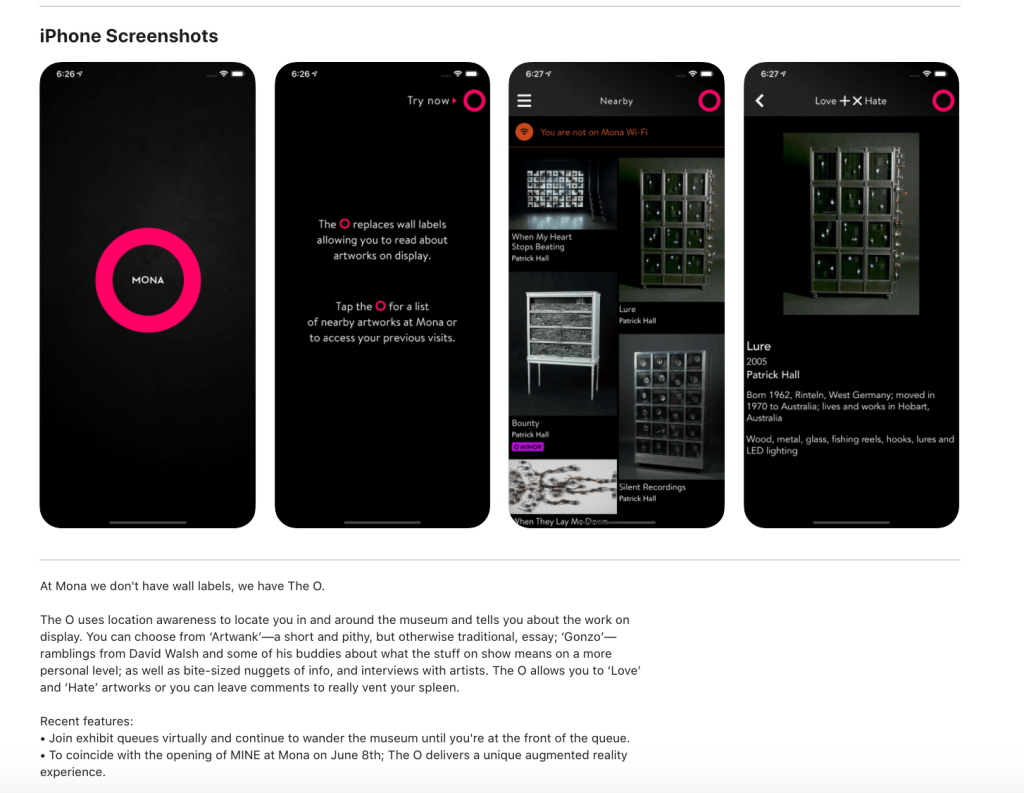

Museums host historical artefacts which require information for a visitor to be able to understand the significance of the item and then to assign meaning (Micha and Economou, 2005, p. 189) Historically museums have used “static” methods of providing explanatory information, including booklets, catalogues and labels (Martin, n.d.). In the South Australian Museum today we have seen the advent of VR technology (see the David Attenborough Great Barrier Reef exhibition that closed recently); use of interactive tablets (see their tablet based treasure hunt, The Shadow Initiation. More information on this one can be accessed on their website: https://www.samuseum.sa.gov.au/event/the-shadow-initiation.) The Museum of Old and New Art in Tasmania lets you have a free iPhone with headphones and when you are in front of an art piece will play you a recording of information about that piece from the artist, the MONA owner or a critic. Alternatively you can download the MONA app on your own smartphone and receive the same experience. I had a similar experience all throughout Moscow, where their major government owned galleries and museums provided either a device to provide you with a tour/information or you could download the same experience straight to your smartphone for free. Importantly, MONAs platform supports VoiceOver to allow disabled, blind and dyslexic people to access the service easily. See the below screenshot of the app page for this app and the following links for further information: https://mona.net.au/museum/the-o; https://apps.apple.com/au/app/the-o/id1161982400.

The use of personal digital assistants is growing rapidly in museums, and has obvious benefits where this is free, including making the public resource of the museum broadly accessible – especially in cases of language barriers such as my experience in Moscow having English among a dozen other languages provided on the PDAs. Of course security issues stem from this. Dara’s herself points out the inevitable risk of security breach of the networks that PDAs can be subject to. The intellectual property of the data that is contained on the PDAs in reference to museum produced or owned information is vulnerable to cyber attacks, an issue perhaps neglected by Dara in her analysis of the use of stolen data (Pryor, 2017). Additionally, member details including any financial data (donations, as well as on site purchases) may be subject to cyber security breaches also (Burke, 2019, pp. 160-161; Northrup, 2015; Pryor, 2015).

Limiting what users can access on PDAs which guide them through the museum using a management system will go towards preventing downloading malware after authentication has been performed by the user (Burke, 2019, o. 157; San Nicholas-Rocca and Burkhard, 2019, p. 61). Monitoring user access management continuously is critical to ensure the functioning of such restrictions from the internal viewpoint. Firewalls also protect from outside threats (Burke, 2019, p. 158). To protect the intellectual property from corruption or erasure back ups of information are critical in what Pryor (2017) refers to as ICT disaster recovery planning.

References:

Apple Application Store. (2020). The O app. Retrieved from: https://apps.apple.com/au/app/the-o/id1161982400.

Burke, J. (2019). Protecting Technology and Technology Users. In Burke, J. (ed.) Neal-Schuman library technology companion: A basic guide for library staff (6th ed.) (pp. 155-162). New York: American Library Association.

Dara, R. (2019). The dark side of Alexa, Siri and other personal digital assistants. Retrieved from: https://theconversation.com/the-dark-side-of-alexa-siri-and-other-personal-digital-assistants-126277.

Martin, J. (n.d.) From the static to dynamic: The evolution of museums and galleries. Retrieved from: https://www.quantumrun.com/article/static-dynamic-evolution-museums-and-galleries.

The Museum of Old and New Art. (2020). THE O. Retrieved from: https://mona.net.au/museum/the-o.

Micha, K. and Economou, D. (2005). Using Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs) to enhance the museum visit experience. In Bozanis, P. and Houstis, E.N. (eds.), 10th Panhellenic Conference on Informatics, PCI 2005 (pp. 188-198). Volas, Greece: Springer.

Northrup, L. (2015). Zoo and Museum Gift Shop Operator Confirms Details of Payment Data Breach. Consumerist. Retrieved from: https://consumerist.com/2015/10/15/zoo-and-museum-gift-shop-operator-confirms-payment-data-breach/.

Pryor, W. (2017). Staying safe: cybersecurity in modern museums. MW17: MW 2017. Retrieved from: https://mw17.mwconf.org/paper/staying-safe-cybersecurity-in-modern-museums-internal-external-and-hidden-threats-with-a-focus-on-cryptography-to-maintain-data-security/.

San Nicolas-Rocca, T. and Burkhard, R. J. (2019) Information Security in Libraries, Information Technology and Libraries, 38(2), 58-71. doi: https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v38i2.10973.

South Australian Museum. (2020). The Shadow Initiation. Retrieved from: https://www.samuseum.sa.gov.au/event/the-shadow-initiation.

Good discussion of the benefits of PDAs and also some security strategies that museums can employ. Your discussion is well supported by literature and concrete examples at the SA Museum.

LikeLike