How are public libraries responding to the issue of digital inclusion and people with disabilities?

What technology are they using and / or what changes have been made?

How does it work?

Fitzgerald et. al. notes that both “physical and geographical access to digital technology” (2015, p. 214) must be considered in relation to the issue of digital inclusion. The authors note that Campaspe Regional Library in Victoria has been recognized with an award in relation to their “Being Connected: Libraries and Autism” program which focuses on access to the library for children with autism (p. 226). Some of the measures identified include:

- All staff, including front-line staff, received respite training (p. 227)

- Incorporation of community groups to facilitate events, such as photography clubs (p. 227)

- iPads and Boardmarker online purchased to facilitate communication and integration with the local special needs school (p. 227), otherwise called “mobile interactive learning stations” (Mustey, 2014)

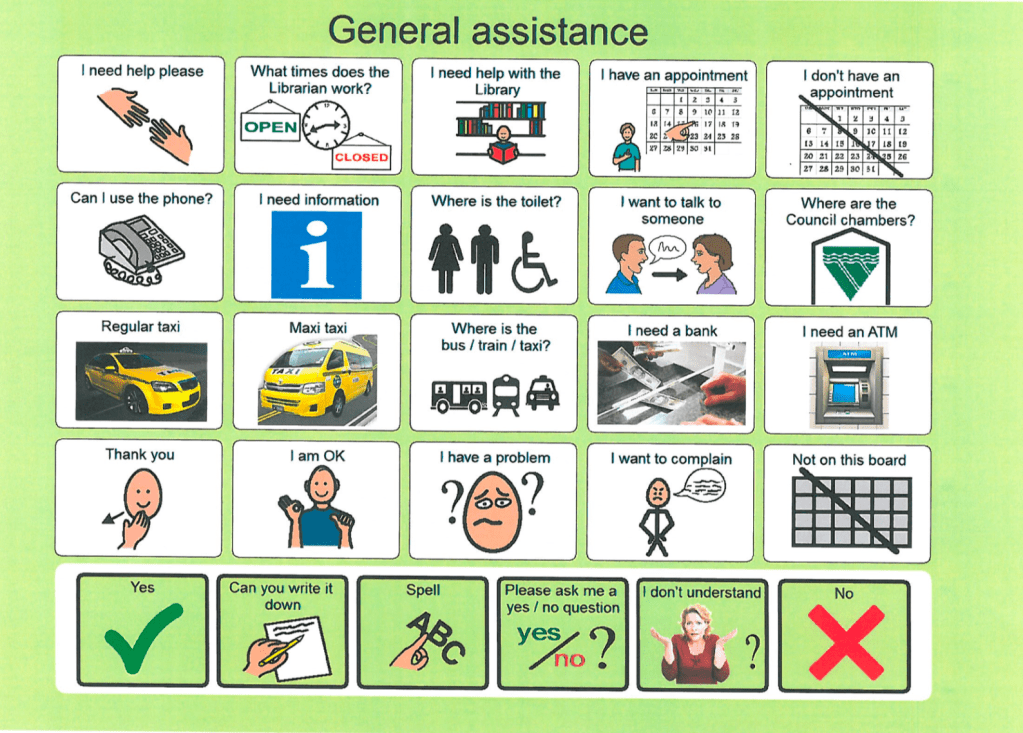

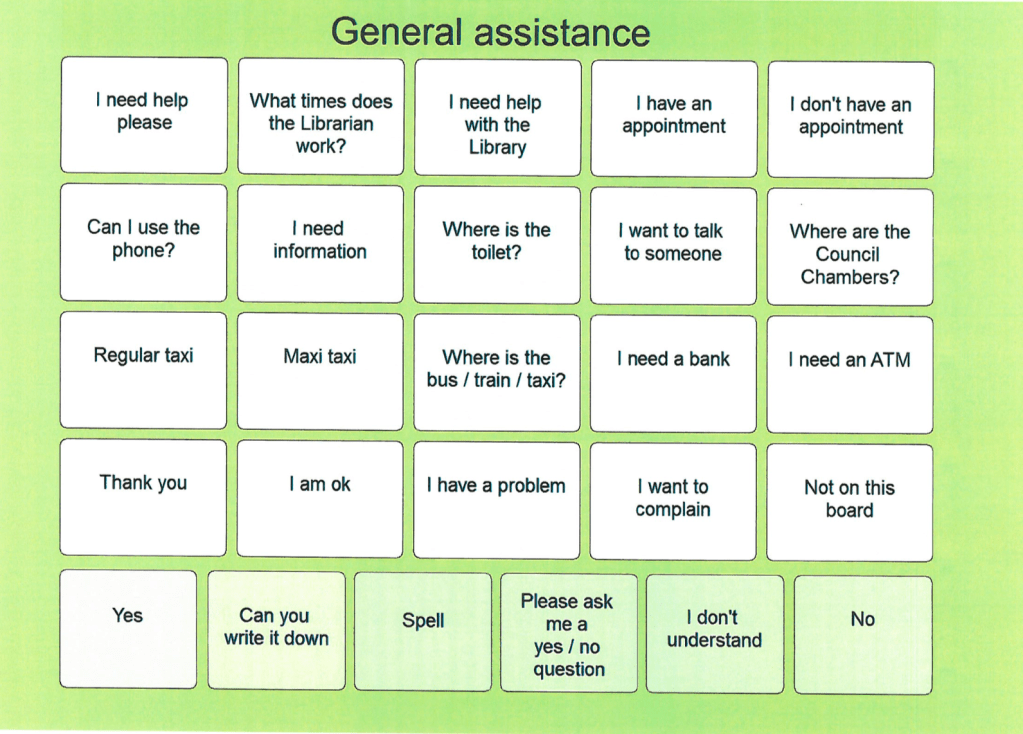

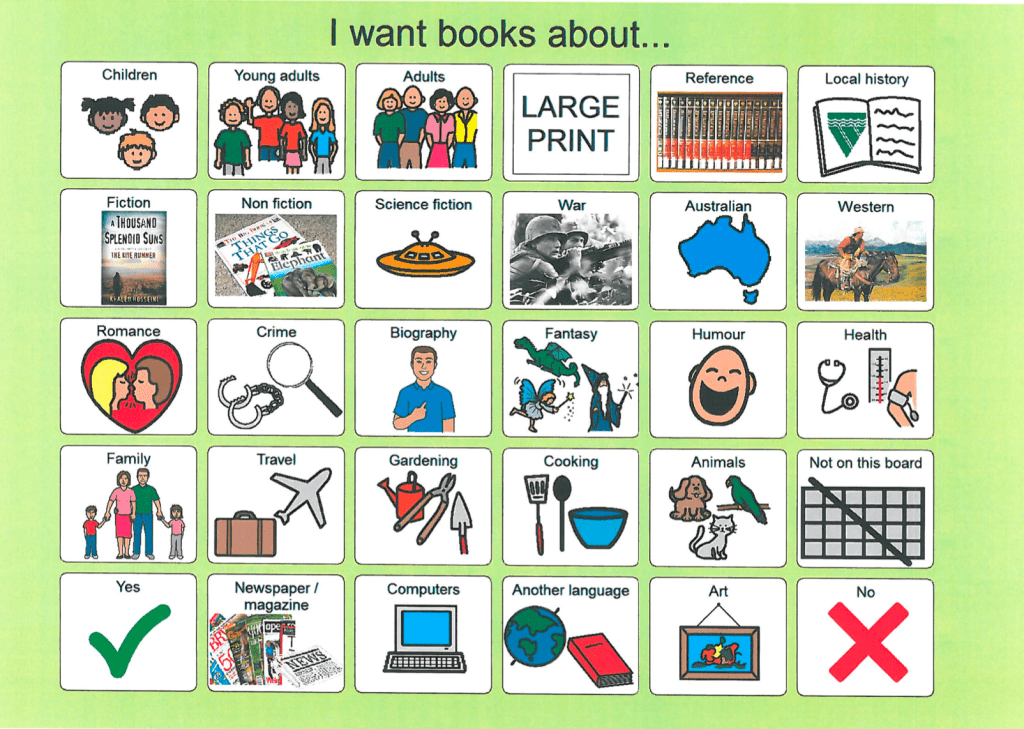

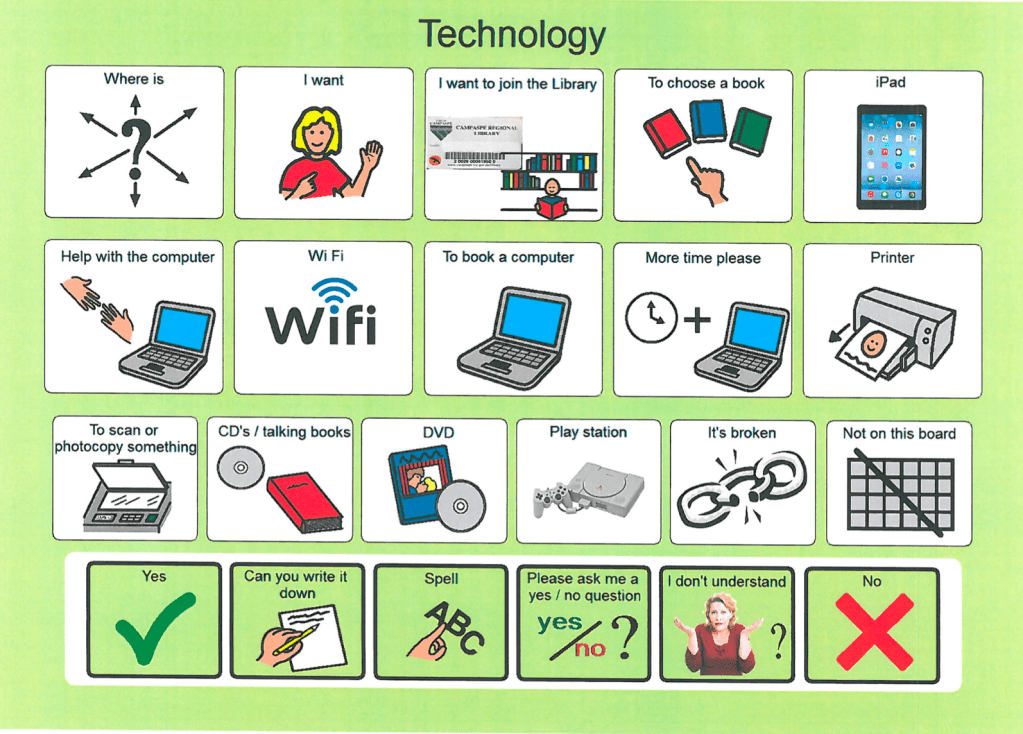

Additionally, Campaspe Regional Library has introduced “communication access boards” for their patrons as per the photos below (Campaspe Regional Library Services, Communication Access, 2019). These boards include a mixture of text and graphic based assistance cues; with high contrast and large graphics used. I would argue that the library has used publishing programs to create a unique tool to assist their patrons with disabilities that affect their communication. Talking newspapers were also introduced (Campaspe Regional Library wins state award, 2018).

Beyond use of technology, the library also introduced the “Next Chapter Book Club” for people with intellectual and physical disabilities. “Echo reading” was used, where book club members who were illiterate would repeat back what was read aloud (Romensky, 2017).

Communication boards

(Campaspe Regional Library Services, Communication boards, 2019).

Who it benefits?

Those who directly benefit from disability inclusion services are of course, those who experience disability. Increasing social and cultural inclusion correlates directly with increased mental wellbeing, and also increased opportunities for economic engagement through the provision of accessible digital devices (Aitken, 2017; Australian Government Department of Social Services, 2012). It also goes towards increases in “pride in their caregiving skills” for carers with increases in accessible means of disability inclusion (Arabit, et. al, 2018; Clover, 2017). Increases in library staff communication skills and confidence have been observed by Henczel and O’Brien in 2011 relation to library staff disability training, with one focus group participant even stating that increases in inclusion in the library setting is “inspirational” (p. 70).

What are the implications for the information service?

Are there any other considerations?

It is disappointing to note that in 2019 the Campaspe Regional Council announced their decision to withdraw from the provision and delivery of disability services within the region (Decision made to withdraw from aged and disability services, 2019). The extent to which this may impact accessible services in the library is yet to be determined by the council, the library and the literature.

Strong and ongoing community leadership and advocacy is needed within the information service of public libraries to secure funding, as well as government receptiveness (Fitzgerald et. al., 2015, p. 229). The lack of research and reporting in the area of the accessibility of libraries in Australia is noted multiple times by Fitzgerald et. al. (2015, p. 232) especially from a local perspective. Libraries and information management academics may need to step up as leaders in this area of research and advocacy, even if informal, in order to drive continued change.

References

Aitken, Z., Krnjacki, L., Kavanagh, A., LaMontagne, M., & Milner, A. (2017). Does social support modify the effect of disability acquisition on mental health? A longitudinal study of Australian adults. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(10), 1247–1255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1418-5.

Arabiat, D. H., Whitehead, L., & AL Jabery, M. (2018). The 12‐year prevalence and trends of childhood disabilities in Australia: Findings from the Survey of Disability, Aging and Carers. Child: Care, Health and Development, 44(5), 697–703. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12588

Australian Government Department of Social Services. (2012). Increasing accessibility library initiative. Retrieved from https://www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/disability-and-carers/program-services/for-people-with-disability/increasing-accessibility-library-initiative.

Campaspe Regional Library Services. (2019). Communication access. Retrieved from: https://cprl.swft.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/cprl/?rm=COMMUNICATION+0|||1|||0|||true&dt=list#.

Campaspe Regional Library Services. (2019). Communication boards. Retrieved from: https://cprl.swft.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/custom/web/content/cprl/CPCommBoards.pdf.

Campaspe Shire Council. (2019). Media Release: Decision made to withdraw from aged and disability services. Retrieved from: https://campaspe.vic.gov.au/council/news-and-media/media-releases/2019/10/16/decision-made-to-withdraw-from-aged-and-disability-services/.

Campaspe Shire Council. (2018). Media Release: Campaspe Regional Library wins state award. Retrieved from: https://www.campaspe.vic.gov.au/council/news-and-media/media-releases/2018/05/18/campaspe-regional-library-wins-state-award.

Clover, D. (2017). Meeting the needs of parents and carers within library services: responding to student voices at the University of East London. Retrieved from http://roar.uel.ac.uk/6001/1/Clover%20Meeting%20the%20needs%20of%20parents%20and%20carers.pdf.

Fitzgerald, B., Hawkins, W., Denison, T., & Kop, T. (2015). Digital inclusion, disability, and public libraries: A summary Australian perspective. In B. Wentz, P. T. Jaeger & J. C. Bertot (Eds.), Accessibility for persons with disabilities and the inclusive future of libraries, Advances in Librarianship, 40, 213 – 236. DOI 10.1108/S0065-283020150000040019

Henczel, S, & O’Brien, K. (2011). Developing Good Hearts: The Disability Awareness Training Scheme for Geelong Regional Libraries Staff. Australasian Public Libraries and Information Services, 24(2), 67–73.

Mustey, J. (2014). Pierre Gorman award goes to Campaspe libraries. Incite, 35(4), 12–13.

Romensky, L. (2017). Book club with a difference launched in Echuca. Retrieved from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-03-17/australias-first-next-chapter-book-club-launched-in-echuca/8361508.